PRIMARY URL

USCGAUX EVENTS:

AUXILIARY MEETING

Meeting Time: 6:30 p.m.

HR Website

Lines and Knots

Thursday, 31 December 2020

Sunday, 20 December 2020

Friday, 18 December 2020

Coast Guard Holiday Party Snapshots - Dec. 16

The 2020 Coast Guard Holiday Party was a unique one this year, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead of being held at the hotel, it was hosted on December 16, 2020 at Sector Guam. Wearing our now familiar face masks, we took a couple of snapshots. Enjoy, and please stay safe!

VFC/FSO-DV Mendiola Expresses Her Gratitude

Tuesday, 15 December 2020

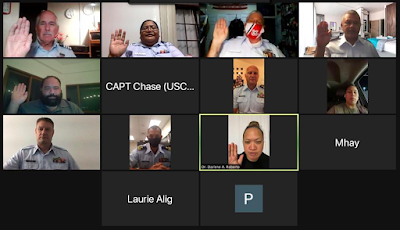

USCGAUX Guam Flotilla Staff Officers Sworn In by Captain Chase - Dec. 15

Congratulations to the USCG Auxiliary 2021 Guam Flotilla Staff Officers who were sworn in today via Zoom by Sector Commander Captain Christopher Chase! Also in attendance were Commander Joshua Empen, Master Chief David Fedison, LTJG Ed Oingerang, Guam FSOs, and members. Good luck, and stay safe, Team!

Sunday, 6 December 2020

Wednesday, 2 December 2020

USCGAUX D14 Elected Officers Sworn In - Dec. 3

Wednesday, 25 November 2020

Sunday, 22 November 2020

Swearing-In Ceremony - Dec. 03 at 1600 (Guam & Saipan Time)

A swearing-in ceremony for all elected officers via ZOOM will be attempted on Wednesday, December 2, 2020 at 2000 hours (HST). On Guam and Saipan, it will be on Thursday, Dec. 03 at 1600. DNACO will do the honors if available. Swearing In ceremony to be recorded for Auxiliary members unable to attend.

All officers should be wearing the Tropical Blue uniform with accompanying ribbons, devices and shoulder boards appropriate to their newly-elected status. Covers need not be worn since it is assumed all will be indoors. Elected officers may invite their respective appointed officers to also be sworn in at this time, but for those who may not be able to participate, their oath of office can be administered by Flotilla or Division elected officers at a later date/time.

Please look for an e-mail from COMO Zwicky with the appropriate ZOOM link to join the ceremony in early December.

Congratulations to all, and here’s to a productive Auxiliary year to come.

Condolences for the Mendiola Family

Daily rosaries are being held daily from Nov. 22-29, 2020 at 12:00 p.m. (8:00 p.m. CST) via Zoom, Meeting ID: 691 692 2160. There is no password required. Kindly enter with cameras and mics off to conserve bandwidth and prevent audio feedback.

The mass of intention for Rick will be at the San Vicente Catholic Church, Barrigada on Sunday, 10 a.m.; Weekdays, 6:00 p.m., & Saturday, 7:15 a.m. Funeral information will be announced later. Si Yu’os Ma’ase’ for keeping the Mendiola family in your prayers.

Monday, 16 November 2020

USCGAUX Change of Watch Meeting - Dec. 8

Tuesday, 10 November 2020

Happy Veterans Day!

Monday, 9 November 2020

Friday, 6 November 2020

Monday, 26 October 2020

Wednesday, 21 October 2020

Tuesday, 20 October 2020

Tuesday, 13 October 2020

Tuesday, 6 October 2020

Thursday, 1 October 2020

Half-masting of national ensign in honor of DHS personnel who have died due to COVID-19

TO ALCOAST

UNCLAS //N05060//

ALCOAST 371/20

COMDTNOTE 5060

SUBJ: HALF-MASTING OF NATIONAL ENSIGN

A. U.S. Coast Guard Regulations 1992, COMDTINST M5000.3 (series)

1. As directed by the Department of Homeland Security Acting Secretary,

the national ensign shall be flown at half-mast on Thursday, October 01, 2020

from sunrise to sunset, in honor of DHS personnel who have died due to COVID-19.

2. The national ensign shall be flown at half-mast on all U.S. Coast Guard

buildings, grounds, and vessels not underway.

3. If normally flown, the Department of Homeland Security flag shall also be

flown at half-mast for the same duration.

4. Internet release is authorized.

Thursday, 24 September 2020

Guam’s first Coast Guard Fast Response Cutter arrives at Apra Harbor

The Coast Guard Cutter Myrtle Hazard (WPC 1139) arrived at its new homeport in Santa Rita, Guam on Thursday.

The crew of the Myrtle Hazard traveled from Key West, Florida to Guam, covering a distance of over 10,000 nautical miles during the two month journey.

The new Fast Response Cutter (FRC) is the first of three scheduled to be stationed on Guam and replaces the 30-year old 110-foot Island-class patrol boats. FRCs are equipped with advanced command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems and boast greater range and endurance.

“FRC’s in Guam strengthen and affirm the U.S. Coast Guard’s operational presence in Oceania,” said Lt. Tony Seleznick, commanding officer of the Myrtle Hazard. “We increase the fleet’s range, endurance, and capabilities to deter illegal behavior, support Search and Rescue, promote maritime stability, and strengthen partnerships.”

The FRCs represent the Coast Guard’s commitment to modernizing service assets to address the increasingly complex global Maritime Transportation System. Like the Island-class patrol boats before them, the Myrtle Hazard will support the people of Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and our international partners throughout Oceania.

FRC’s are designed for various missions including drug interdiction, defense operations, maritime law enforcement, search and rescue, marine safety, and environmental protection. FRC’s can reach speeds of up to 28 knots and endure 5 days out at sea while covering over 2,500 nautical miles.

“Myrtle Hazard will significantly increase the capabilities of the Coast Guard throughout the region,” said Capt. Chris Chase, commander, Coast Guard Sector Guam. “I am excited to welcome the crew of the Myrtle Hazard home and look forward to them conducting operations with our partners in the near future.”

Myrtle Hazard, the cutter’s namesake, was the first female to enlist in the Coast Guard. Enlisting in January, 1918, she became a radio operator during World War I. She ended her service in 1919 as an Electrician’s Mate 1st Class.

Each FRC has a standard 24-person crew. This will bring over 70 new Coast Guard members to Guam, along with a projected 100 family members. In addition to the crews of the three ships additional Coast Guard support members and their families will also be in Guam.

Sources: USCG News Release & Pacific News Center

Saturday, 19 September 2020

Applications for National Staff Positions Now Being Solicited- Deadline is 30 September

National Commodore elect, Alex Malewski, is pleased to announce his selections for ANACO and Director for the 2020-2022 term, and to solicit applications for all lower level staff positions.

ANACOs

Chief Counsel (CC) – Douglas Cream

Diversity (DV) – David Porter

Chief Financial Officer (CFO) – Robert Bruce

Response and Prevention (RP) - Kevin Cady

ForceCom (FC) - Gregory Kester

Recreational Boating (RB) - Robert Laurer

Planning and Performance (PP) - Peter Jensen

Information Technology (IT) - Susan Davies

Directors

DIR-R Response: Roy Savoca

DIR-P Prevention: Kim Cole

DIR-Q Emergency Management and Disaster Response: Anthony Marzano

DIR-I International Affairs: David Huang

DIR-A Public Affairs: Lourdes Oliveras

DIR-T Training: Gerlinde Higginbotham

DIR-H Human Resources: Lee Zimmerman

DIR-V Vessel Examination: Christopher Wilson

DIR-E Public Education: David Fuller

DIR-B RBS Outreach: James Cortes

DIR-S Strategic Planning: Jeannemarie McNamara

DIR-M Performance Measurement: Kevin Redden

DIR-C Computer Software and Systems: Amanda Constant

DIR-U User Support and Services: Gerald (Randy) Patton

Members desiring appointment or reappointment to the National Staff for deputy or below positions are invited to submit a resume and relevant information to the appropriate person listed above no later than 30 September. Members desiring appointment must specify the office to which appointment is desired. If more than one office is sought, apply separately for each one. ANACO and Director email addresses are available in the AuxDirectory (https://auxofficer.cgaux.org/auxoff/unitstaff.php).

Wednesday, 16 September 2020

Sunday, 13 September 2020

D14 2020 Fall Conference A Success!

Bravo Zulu to the D14 conference committee for planning a successful virtual D14 2020 Fall Conference! Although we could not convene together in person, due to COVID-19, our fellowship remained strong, and we were able to increase our knowledge on the various missions, training, etc. the USCG Auxiliary engages in. Kudos to the organizers, presenters, and members who attended this historic event! Stay safe, Team, and enjoy the following snapshots!

Saturday, 12 September 2020

Friday, 11 September 2020

Thursday, 3 September 2020

Tuesday, 25 August 2020

Thursday, 13 August 2020

The Long Blue Line: Ocean Station—Coast Guard’s support for the Korean War 70 years ago!

Coast Guard Cutter Pontchartrain battles heavy seas on Ocean Station duty. (U.S. Coast Guard)

Coast Guard cutter Sebago encounters heavy seas while serving on Ocean Station duty. (U.S. Coast Guard)

Casting a Nansen bottle used to measure ocean water temperatures at various depths. (U.S. Coast Guard)

1) Coast Guard cutter Sebago encounters heavy seas while serving on Ocean Station duty. (U.S. Coast Guard)

2) Former World War II destroyer escort Richey converted to a Coast Guard cutter for Ocean Station duty. Notice depth charge racks and plentiful anti-aircraft armament of this heavily armed cutter. (U.S. Coast Guard)

3) Deploying a weather balloon for U.S. Weather Bureau reports and forecasting. (U.S. Coast Guard)

4) Coast Guard cutter Taney encounters heavy seas en route to its Pacific Ocean Station duty. (U.S. Coast Guard)

Tuesday, 11 August 2020

Valuable Views on Diversity

Saturday, 8 August 2020

Monday, 3 August 2020

Monday, 27 July 2020

The Long Blue Line: Florence Finch—Asian-American SPAR and FRC namesake dons uniform 75 years ago!

SOURCE: http://live.cgaux.org/

Sunday, 19 July 2020

The Long Blue Line: Great Galveston Hurricane—Coast Guard’s first superstorm 120 years ago

-Keeper Edward Haines, Galveston Lifesaving Station,

Sept. 17, 1900